A Land Legacy Forged by the Trans Pecos

Watch the family film on Facebook to hear it from their perspective: https://www.facebook.com/share/v/17BU5y77hc/

C.E. Miller Ranch

The Miller brothers—Albert, Bill, Jim and Walter—measure their riches in space, freedom, experiences and a multi-generational legacy of stewardship forged in the unforgiving, but ruggedly beautiful Chihuahuan Desert landscape of the 11,465-acre C.E. Miller Ranch near Valentine.

“We all grew up out here footloose and fancy free, maybe even feral,” Albert, the oldest brother, said. “Our mother started turning us loose out here before we were six years old and never had any idea where we were, but we never had any incidents just adventures—and a great fondness for the place we call home.”

The brothers are stair steps. Albert was born in 1950, Bill in 1952, Jim in 1954 and Walter in 1956. Their early childhood coincided with Texas’ Drought of Record, a scorching dry spell that spanned most of the 1950s and shaped everyone who lived through it.

“My earliest memories are feeding cattle during the drought and the never-ending dust that boiled up everywhere,” Albert said. “This isn’t easy country when the rains fall, but when they quit it really gets challenging—and we’re in a hard drought again.”

The boys started doing man’s work early on. During that time, the family experimented with a 100-acre irrigated field where they raised sorghum, barley and winter crops, which they chopped into silage.

“The running joke between Bill and me is that in the beginning we fought over who got to drive the tractor but later we fought over who had to drive the tractor,” said Albert, noting the silage was used to feed calves in their family’s feedlot that were destined for local butchers.

Raised in the era of screwworms, the brothers also rode pastures daily, checking and doctoring cattle. In addition to logging a lot of horseback miles, they grew to know the land, the cattle and the wildlife as well as they knew their family.

“We helped operate 30,000 acres of family ranch,” Albert said. “It takes a lot of time to check everything everywhere, but you really get to know a place when you’re on it every day.”

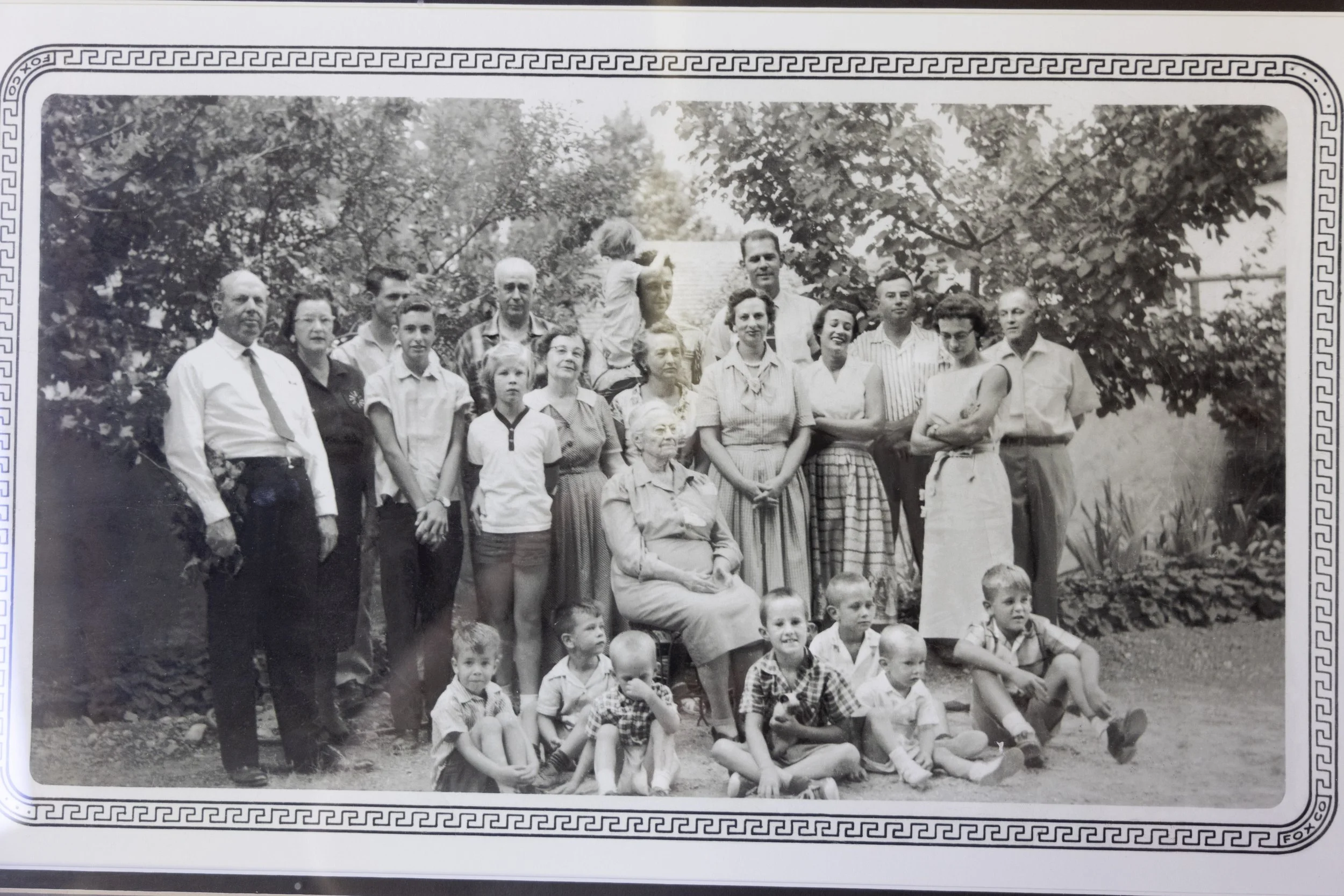

The boys’ first-hand experiences with working the land were reinforced with lessons of resilience, fortitude, and stewardship from their grandparents and parents. Their great-grandfather, Walter Spurgeon Miller, his wife and infant son Clay Espy traveled by wagon train to Fort Davis, Texas, and then moved to Valentine, where W.S. worked on area ranches and in the W. Keesey store. Eventually, W.S. became the principal shareholder of the store, renamed The Union Trading Company, as well as chief stockholder in The Limpia Banking Company and manager of the Limpia Hotel in Fort Davis.

Although his parents were merchants, Clay “Espy” was a rancher at heart and bought his first ranch after returning from World War I. In 1925, the newlyweds Espy and his wife Lucy bought the John Holland Ranch near Valentine, which they renamed the C.E. Miller Ranch. In 1937 and 1948, Espy and his brother Keesey bought neighboring ranches adding to the operation.

“I remember my grandmother telling me that she and my grandfather would lay in bed and she could feel my grandfather’s finger tapping on the bed because he was trying to decide if he wanted to borrow money to buy more land,” Albert said. “It was a big decision, a big commitment and a big sacrifice.”

When the first generation of Millers passed the ranch to their son and two daughters, their son Clay Espy Miller Jr. took the management reins. As a zoologist trained at the University of Texas, Clay, with the help of his wife Jody and their four sons, added a new chapter in the family’s stewardship legacy.

“I like to think of my father as a bit of an enigma in this part of the world,” Walter said. “He was a very much a cow person—that was his business—but he was more of a naturalist. Some would say almost a Renaissance Man. He was very interested in all things scholarly.”

During Clay’s university years, Dr. Frank Blair, 22 fellow students and he spent six weeks collecting small mammals, reptiles, birds and amphibians. The collection is still housed at UT Austin and Texas Tech. In the early 1950s, Clay helped capture pronghorn antelope on the Rocker B Ranch near Mertzon, Texas and relocate them to the Trans Pecos. He traveled to Washington D.C. to testify to protect the Golden Eagle. He and Jody opened the ranch to the Peregrine Fund to help sponsor Aplomado Falcon Restoration.

Avid birders, Clay and Jody recorded more than 300 bird species, including Scaled Quail, Gambel’s Quail and Montezuma Quail. The ranch is home to mule deer, pronghorn antelope, aoudad, javelina, mountain lions, bobcats and coyotes as well as a host of small mammals, reptiles and amphibians.

The wildlife thrives alongside cattle when conditions permit. In optimal years, the ranch can carry 500 Angus mother cows. In response to drought, the family destocked completely in 2021 but hopes to restock when the rain begins to fall again and the land responds.

“We never made much money in our lifetime,” Albert said. “In fact, the only place we made money in ranching is land appreciation, but my brothers and I are together in the belief and practice that we’ll give up a lot to have the ranch to go back to.”

He continued, “We’ve been very fortunate. We have not always had the highest lifestyle, but we’ve had some things nobody else had, things that nobody else could experience.”

Bill concurred, “The most valuable thing we own, if we own anything out here, is space. That’s what people are looking for is space. My brothers and I don’t want to see it covered up with roofs and asphalt.”

In the Trans Pecos, the fragmentation is less visible than along the I-35 corridor, but just as real. Old family ranches are being sub-divided as one generation transitions to another and the number of heirs grows, and the profitability doesn’t. In many instances, family members have competing priorities for the land, so the ranches are broken into smaller units and sold.

Faced with the same challenges, the Miller family thought long and hard about how to transition their ranch intact to the next generation. After sleepless nights and countless long, heartfelt, thought-provoking conversations where they “cussed and discussed” their options, they all agreed that a conservation easement in partnership with the Texas Agricultural Land Trust (TALT) was their best tool for achieving their shared goal.

Walter said, “We were attracted to TALT and this type of easement because it left a lot of the management practices that we had implemented over the years and that we knew worked in place. They let us continue doing what we do.”

The easement funded by the Greater Big Bend Conservation Partnership RCPP, Knobloch Family Foundation, Texas Farm and Ranchland Conservation Program (TPWD), and Horizon Foundation, not only conserved the land in perpetuity but provided an infusion of capital. The additional money allowed the brothers to “step away from the ranch and let the next generation step in.”

“This place will teach you how to do practical things. Out here we learned to be more self-sufficient and get along without a lot of resources,” Albert said. “We learned to get by without things—those are all important lessons for our children and grandchildren as they make their way through the world.”

He continued, “Our grandfather and our father both passed on legacies of conservation because they felt this was where they wanted to live. And we followed the same practice and certainly hope to pass it on to our kids, grandkids and the rest of the family on down the line.

Bill added, “You know, we don’t really own this place. We’re just taking care of it and trying to make it better. You know that’s the aim.”

Thanks to the shared commitment to stewardship, the land and the family, the next generation is fully aware of the legacy with which it has been entrusted.

Clay, Albert’s son who is actively involved in the day-to-day management of the ranch, said, “My grandfather was always very conscientious of taking care of the ranch and his family because the ranch took care of the family. If you didn’t take care of the ranch, you couldn’t take care of the family.

When my grandparents passed, there was a definite change on the ranch because they had been fixtures in all our lives. It seemed like the heart of the ranch had left. But that puts it on us to create that heart again—where everyone wants to come and takes the time to come.

You know, there may come a time when most of Texas is nothing but concrete, there will be children who have never set foot on dirt, and they can come here and set foot on dirt. To me, it’s a huge comfort to know that this piece of Texas will always be this piece of Texas.”