Rooted in Legacy, Committed to the Future

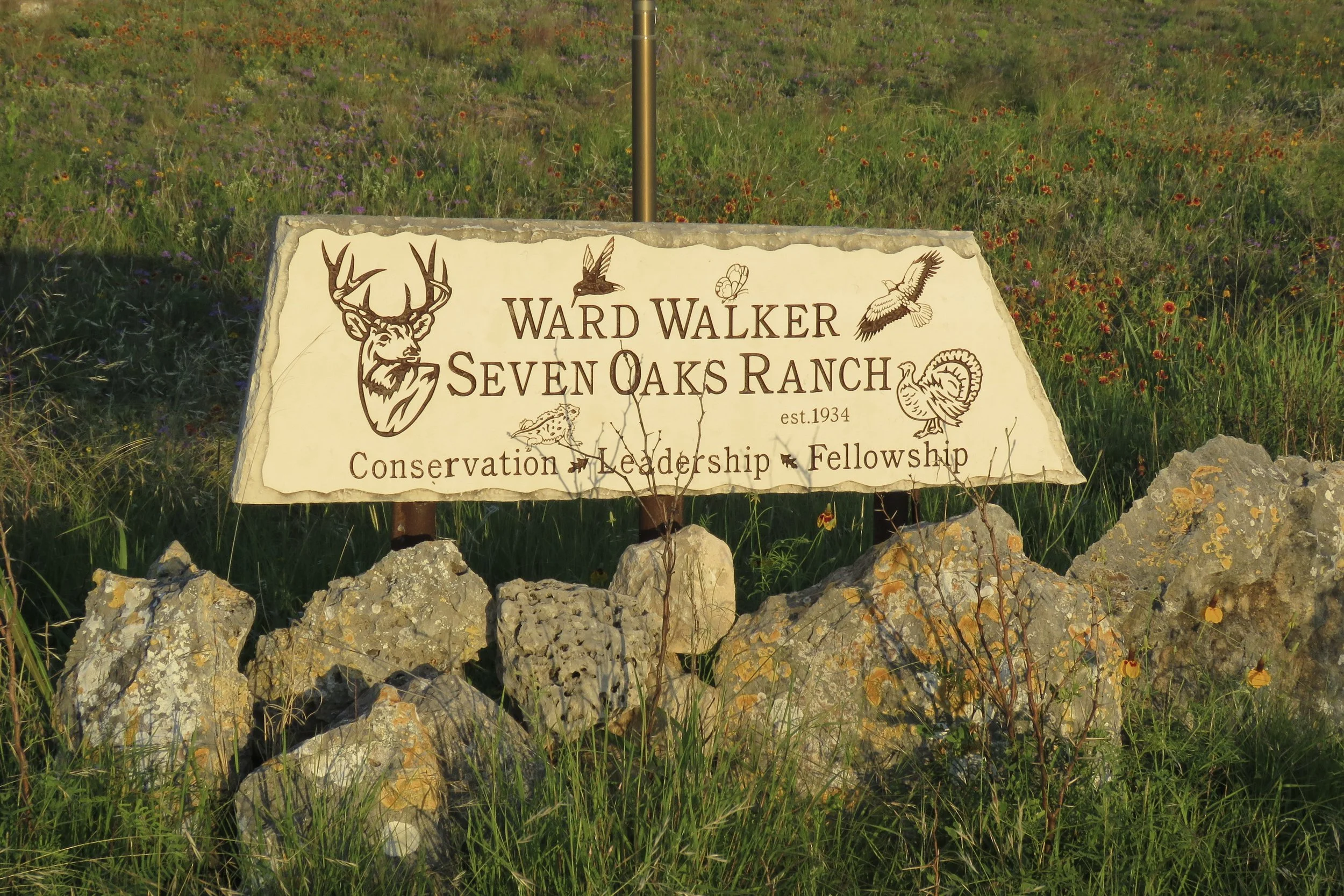

Seven Oaks Ranch

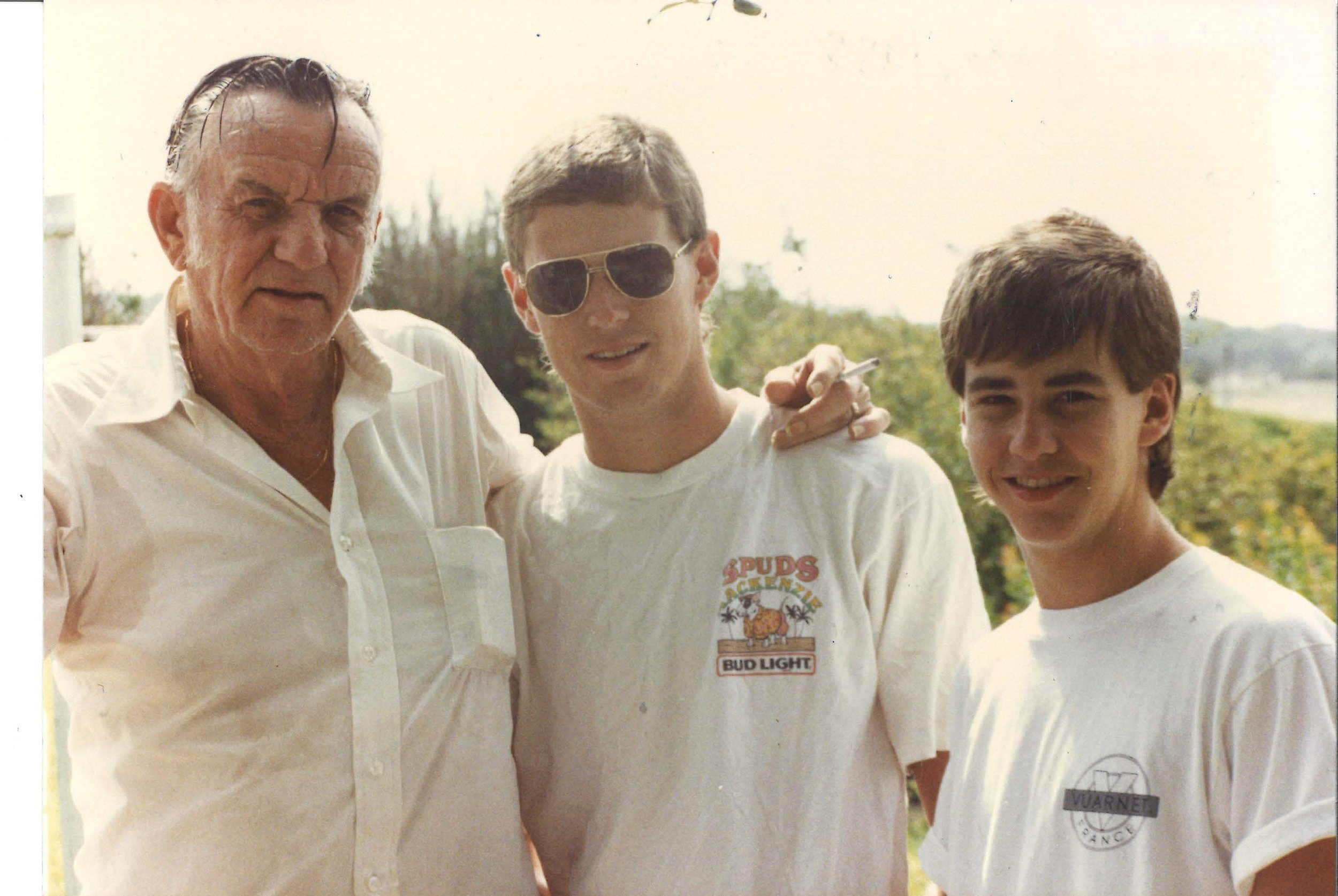

On the front porch at Seven Oaks Ranch, time has always moved a little differently. Long before conservation easements entered the family’s vocabulary, Wayne and Philip Walker learned the land the old way: by sitting still, watching, and listening.

Their grandmother, Ellen Ward, insisted on it.

“She would make us sit out on the porch, the front porch of the ranch house and watch nature and be quiet and observe,” Wayne recalls. “And she would tell us about what roles the animals played, the quail and the turkey, and the squirrels and the birds.”

That porch, and the lessons learned there, would shape not only their childhoods, but the future of the 7,374-acre Ward-Walker Seven Oaks Ranch in Crockett and Val Verde counties, a working landscape now permanently protected by a conservation easement. Wayne and Philip, along with their younger brother Caton, represent the third generation of their family to steward the land.

For Wayne and Philip, the decision to place the ranch under easement was not a single moment, but the culmination of generations of stewardship and years of careful thought.

“To protect our family’s legacy,” Wayne says. “And all the work my grandmother, Ellen Ward, our step-grandfather Jack Ward, and our father Kelly Walker put into the ranch over the years. We don’t want our ranch to get chopped up into subdivisions and ranchettes. And we don’t want it to turn into something that loses the value of what our family has created.”

Philip agrees, adding that gratitude played a central role in their decision.

“We’re grateful to have this land, and I think this is one way to show our gratitude by making sure that it stays the way it is, in perpetuity,” he says. “It’s also a way to put your money where your mouth is and show your values instead of just talking about it. We’re actually doing something meaningful to protect the open spaces, wildlife, archeology, ranching heritage and dark skies into the future.”

Seven Oaks has long been more than acreage on a map. Once part of the original Kincaid Ranch Empire assembled in the early 1900s, the land has seen shifting management philosophies, hard lessons learned, and a slow, deliberate evolution toward conservation-focused stewardship. Prescribed fire, reduced livestock herd size and rotational grazing, habitat restoration and education have become hallmarks of the ranch’s identity, work that earned the family statewide recognition, including being honored with a prestigious Lone Star Land Steward Award from Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. But the conservation easement represents something deeper than accolades.

“Open space and the ecosystem services it provides has worth,” Philip says. “Raw land has value but society doesn’t recognize that value economically for the most part. You don’t need to build things on it for it to be worth something. It has value for protecting wildlife and plants, dark skies, clean and ample water and air, and life in general. And letting the ecosystem work the way it always has.”

That philosophy has guided decades of decisions at Seven Oaks, from restoring fire to the landscape to welcoming the next generation of the family as well as students, volunteers, and conservation partners onto the ranch. Philip has led many of those efforts, opening the gates to college burn crews, wildlife researchers, and nonprofit partners.

“We want to continue public outreach, education, fellowship and innovation,” he says. “How can we help get people outdoors? How can we help teach them how the world really works? It’s not in your cell phone. It’s clean water, open land and dark skies at night the way they used to be.”

Fire, in particular, has become both a management tool and a gathering point.

“Fire has always represented fellowship,” Philip explains. “If it’s a wildfire, people come together to fight it. If it’s a campfire, they’re having fellowship around it. If it’s a prescribed fire, they’re coming together as well to help restore and maintain the land. People put their cell phone down for that, especially the young ones!”

For Wayne, education is the true measure of success. As they have learned from one of their mentors, Dr. Butch Taylor, “Until we’ve educated the next generation, we are not successful,” he says. “Putting the easement on the ranch is a huge step. But it’s not the end.”

The decision to pursue a conservation easement was not without complexity. Like many multi-generational ranch families, the Walkers navigated deeply rooted attitudes about land ownership, skepticism about outside entities, and the emotional weight of honoring those who came before them.

“Our step-grandfather, Jack Ward, was very leery of the federal government and the state government at times. This likely came from when he had to help move his family (Homer Wilson Ranch) out of Big Bend National Park when that land was purchased from the Federal Government,” Philip says. “That mentality is still out there. But you have to get educated. Everything is not the same for everyone. If your intent is good, that’s everything.”

Through their work with Texas Agricultural Land Trust, the family found a patient partner who addressed concerns one by one and helped ensure the easement reflected—and would protect—their values and long-term vision for the ranch.

Bringing the easement to completion also required patience and trust within the family itself, and Wayne and Philip credit much of that progress to Dallas J. Barrington of Beaumont, who helped guide the Walkers through difficult conversations and legal complexities during a period of transition.

“He’s just got this gift,” Wayne says. “He’s a very good lawyer, but more than that, he helped us get through the hard times as a family.” Today, Barrington serves as the ranch’s sole manager, a role Wayne and Philip say has brought stability and clarity at a critical moment for Seven Oaks.

Wayne believes previous generations would ultimately understand, and approve of, what the family has done.

“I think Dad would be real proud of how we’ve navigated things since we lost him,” he says. “This isn’t the finish line, but it’s a major step. And obviously, Grandmother would be elated and Jack Ward would be, too.”

The easement also reflects a belief that landowners are in a unique position to make a difference.

“We can’t control what the whole world does,” Philip and Wayne say. “But we can control what we do on our ranch.”

That conviction guided their partnership with Texas Agricultural Land Trust, selected for its rancher-first approach and deep understanding of working lands. It also underpins the Walkers’ hope that Seven Oaks can serve as an example for others.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there about conservation easements,” Philip says. “I would hope our decision would inspire and help motivate others to look into them. Depending on your goals and values, this can absolutely be the right decision.”

It takes time, he acknowledges. It takes questions, patience, and finding the right land trust.

“Instead of listening to their friends at the local coffee shop,” Philip says, “call the land trust. Get the knowledge directly from the source. Then make an educated decision.”

For Wayne and Philip Walker, the hope is simple and enduring: that others who love their land as deeply as they do will see what is possible, and choose to act.

“We’re just trying to do our part,” Philip says. “And we hope it inspires others to do the same. After all, we aren’t making any more land so we need to protect every acre we can for current and future generations.”

Partial funding for this project was provided by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department through the Texas Farm and Ranch Lands Conservation Program.